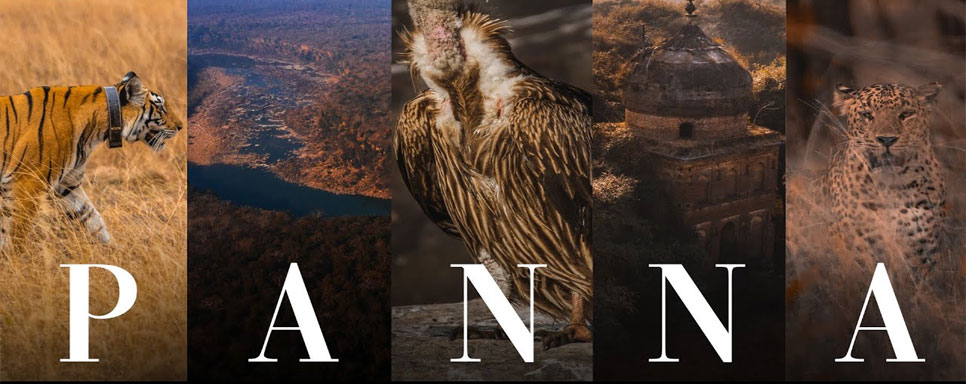

The Rise, Fall and Rise Again: Tigers History at Panna National Park

By JAGAT (15/July/25)

Pre‑1981: From Royal Grounds to Wildlife Sanctuary

Panna’s wilderness originated as princely hunting grounds for Panna, Chhatarpur, and Bijawar rulers under British India. In 1971, a wildlife sanctuary emerged, later expanded and officially designated Panna National Park on October 17, 1981. The park now spans roughly 542. Square kilometre within a larger 1,679 Square kilometre tiger reserve.

Year 1994–2002: Hopeful Beginnings Started

In 1994, Panna became the 22nd tiger reserve under India’s Project Tiger framework. This period marked hopeful growth with tiger density rising from approximately 2–3 per 100 Square kilometre to over 7 by 2002. Prey populations—chital, sambar, nilgai—and water from the Ken River sustained this recovery.

Year 2003–2008: Poaching Crisis and Collapse

The early 2000s brought escalating threats: poaching, habitat encroachment and disturbances from insurgents and dacoits weakened protection efforts. Between 2006 and 2008, nine out of eleven breeding females disappeared. By December 2008, only a single male was sighted—and by early 2009, Panna was declared tiger‑free

Year 2009–2011: The Bold Reintroduction Strategy

A decisive program began in March 2009, relocating two tigresses—T1 from Bandhavgarh and T2 from Kanha. In November- a male, T3 arrived from Pench but attempted to return home, traveling over 440 km. Local villagers, guided by forest staff, rallied to ensure his return and adaptation. Success followed: on April 16, 2010, T1 birthed four cubs—the first proof of reproduction after reintroduction. T2 followed with her first litter in late 2010. Supplementing this were two semi‑wild orphaned tigresses: T4 in March 2011 and T5 in November 2011. Both integrated into the wild and bred successfully. These initiatives marked a pioneering “rewilding” model.

Year 2012–2020: Population Growth & Ecological Restoration

The tiger population steadily increased at approximately 7% annually. By 2019, around 50 tigers roamed the reserve. In 2023–24, the count reached approximately 70–80 animals. Villagers around 59 buffer‑zone hamlets became actively involved—joined “Friends of Panna” initiatives, trained as guides and partnered in patrols—fostering conservation ownership. Forests saw richer prey dens; monitoring intensified with GPS collars, camera traps, and vigilant patrols. As one local tourist’s user praised: “Madhya Pradesh Forest Department and Panna Tiger Reserve have shown how to take steps in atoning for the crimes … a forest which had lost its keystone species in 2008 has over 80 of the big cats now".

Year 2021‑2025: Genetic Dispersal, Regional Benefits and New Challenges

Genetic diversity flourished as tigers dispersed to nearby reserves—Sanjay, Satpura, Ranipur, and beyond. Individual tigers like P243, weighing 228 kg became emblematic of the population's robustness. But conservation brought new challenges: territorial clashes (Tiger 643 sustained head injuries in March 2025, monitored and treated via elephant patrols), cub mortality investigations (one of Tigress P‑141’s four cubs went missing in March 2025—forest staff actively engaged in inquiry) and habitat threats from proposed river‐linking projects.

Matriarch Legacies: T1 and T2

T1 (“grand matriarch”), deceased in early 2023, had produced 13 cubs across five litters, significantly contributing to the population surge. T2, the iconic “Mother of Panna,” died May 28, 2025 at age 19. She bore 21 cubs in seven litters; her four‑generation lineage now encompasses over 85 descendants nationwide. Her longevity and lineage underscore the program’s success.

Why Panna’s Revival Was Possible

Key factors include: • Strategic translocations: Benefit from genetic diversity by sourcing tigers from Bandhavgarh, Kanha and Pench. • Community-driven conservation: Surrounding villagers supported collaring and patrolling, evidencing effective “Jan Samarthan se Bagh Samrakshan” (“people’s support for tiger conservation”). • Vigilant protection: Arrests, patrol strength and anti‑poaching vigilance reversed earlier losses. • Strong ecological base: Healthy ungulate stocks and perennial water from the Ken River sustained the tiger ecology.

Panna now serves as a model for global conservation. Scientific monitoring, community synergy, and strategic planning underpin its resilience. However, sustaining this success requires balancing tourism pressure, managing human–wildlife conflict, and protecting core habitat from development or alteration, such as river-linking. Collaborative management, regular census updates and early intervention in health/habitat issues will be critical to its future.

Panna’s tiger narrative—from extinction in 2009 to a vibrant population of 80+ by 2025—stands as a protection marvel. It highlights how innovative rewinding, genetic stewardship, community dedication and robust habitat protection can overcome human-induced collapse. The legacies of T1 and T2 endure through their cubs, echoing hope in every growl. Panna isn’t just restored—it’s reborn, flourishing as a beacon for tiger reserves worldwide.